Imagine 2036

Hi folks,

Tis the season – the fundraising season, that is! And in this season, I like to share with you a little bit of what inspires me to be here after almost 3 years. Please read my campaign below, and feel free to go to the site and donate to my campaign. If you don’t have money to support me, I also accept encouraging comments, personal emails and care packages!

Thanks for all your love and support,

Erin

Those who know me will agree that one of my strongest values is fairness. My whole life, I haven’t been able to handle it when THINGS. JUST. AREN’T. FAIR. When people jump in line ahead of you. When one person gets a bigger “half” of a snack (good thing we employed the “you cut, I choose” rule in the Antcliffe household!). When men earn more money than women for the same work. When the country you’re born in determines most of how your future will play out.

I see a lot of unfairness in my work as the AgEx Team Leader in Ghana. After 2.5 years, I’ve even become desensitized to it a little bit. But then something happens, and that fairness value blows up inside of me – it’s just not fair! Like when I see how easy it is for me to get a visa to visit Ghana, and how difficult it is for a Ghanaian to visit Canada. Or when I see children show up to school but the teacher doesn’t, thereby depriving those students of their right to education. Or when the women at the office are expected to serve the workshop lunch to the men, but never the other way around.

Often I hear, “but Erin, life’s not fair“. No kidding. But does that mean we should accept inequalities and move on with our lives? I don’t think so!

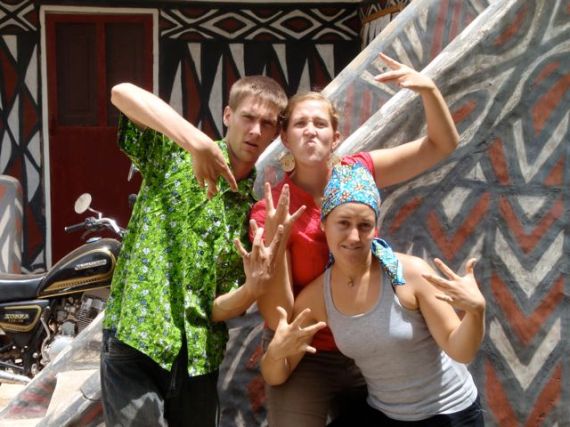

My dream for 2036 is for fairness. I dream that every child in Ghana today, like Hakim, Maliki and Wekaya in the photo above, will have access to the same opportunities as their equals in Canada. I dream that hard work will determine one’s success more than the circumstances of one’s birth. I dream that getting ahead doesn’t mean pushing others down. I dream of a world that presents fair and equal opportunities to allow every member of the next generation to prosper.

I will spend every day of my life working for fairness. This is a value I will always hold, whether I’m working in Africa or Canada. Please join me in working toward my dream of fairness by making a contribution to my campaign.

On Leadership

It’s been several months since I’ve written here. There have been ups and downs and rough patches, but I haven’t felt compelled to share these with the wider world. Just suffice to say it’s been a bit crazy around here since November.

Loyal readers will remember that I was writing last year about my EWB team’s strategy development process. A lot has changed since I last wrote, but I’m not going to try to summarize all of it today – I’m sure it will keep changing at a rapid pace. Instead, I want to write about my personal reflections on this process.

I’ve been reflecting a lot on our strategy lately, and on my role in developing it. I’m now a Team Leader for the Agricultural Extension (AgEx) team in EWB. With this leadership role comes a lot of responsibility, and I’ve been learning a lot about what kind of responsibility I thrive with and where I think I fall short. For example, I love the administrative responsibilities of managing a team. I also love the opportunity to invest in the personal and professional growth of every member of my team. Those aspects of my job are thrilling! I am also thrilled by thinking about the “big picture” of the sector we’re working in and how we’re making change in that sector. But that is also where I struggle the most.

I was told when I took this role that one of my challenges would be developing a strong vision and leading people toward it. That prediction has proven to be very true. I am someone who has always excelled more at poking holes in ideas than in building them up myself. I always chalked it up to a lack of creativity, but there’s more to it than that. My naturally critical mind can think of a million different ways for a project to fail. That makes it pretty damn hard to design a solution that I truly believe in, and even harder to sell it to a whole team of people who are here to commit years of their lives to realizing that vision.

Our team has landed on a ~20-year vision of an agricultural extension sector that is innovative, coordinated and customer-service oriented. We’ve imagined a competitive market where extension service providers come from the public, private and civil society sectors to meet the needs of different segments of customers (farmers) to promote socially and environmentally sustainable agriculture. We see quality being added to these extension services at many points, from training and education, to a strong management structure, to well-developed field tools and approaches, to a strong enabling policy environment. And this vision has me PUMPED UP!!

But how do we get there? That’s where it gets a bit more messy. To dig into that question, our team has been designing a Theory of Change (see some great posts on Theory of Change by Duncan Green from Oxfam). We started by identifying 8 key changes that need to happen in order for our vision to be realized, then worked backward to understand the steps needed to realize these changes. We are still working on that part, but the hope is that the Theory of Change will define where our team needs to work in order to realize our vision in 20 years.

So we have a strong vision, we have a Theory of Change, now we need to get started. And this is where I get stuck. How do we, the five members of EWB’s AgEx team, create the change we want to see in the extension sector? There are seeeeeerious challenges ahead. Most of the major changes in the agric sector are created by those with money, power, political influence, or (more often) a mix of all three. We have none of those things. So how do we change the system?

We need to build a solution. Not just a theory, not just our assumptions and hypotheses, but an actual work-plan for how to move forward. Where should I post the new staff I’ll be getting in June and September? Who can they work with? Will their placements be based on learning, or experimenting, or scaling, or influencing? What about the staff on the ground right now? Who are the most influential partners we should be working with? How do we get others to start thinking about extension in the same way we’re thinking about it? Questions swirling in my mind… and very few answers.

Now, back to my struggles as a (non-)visionary leader. What does this mean for my ability to lead my team toward our exciting-yet-difficult-to-attain future? (Stick with me, I’ll land soon.)

I remember someone asking me a few years ago about my Principle of Leadership. At the time, I stammered and mumbled and generally had no idea. But the question has stuck with me and now I know my answer: my strength as a leader is defined by my ability to leverage the strengths of my team. This is really the principle I rely on in all situations. I have some strengths, but I also have lots of weaknesses, and it is only be relying on my team that I am able to bring the best out of us as a whole.

I look to Robin for bringing unbridled passion for the public sector and making sure we always connect our work to poor farmers. I rely on Miriam to bring insights and approaches from her background in development studies. I lean on Siera for a connection to current field realities from being embedded with extension staff and farmers. I depend on Don for his selfless work ethic and insane networking skills to find new partners for our team.

I am grateful for all of these people, and all those I have worked with in the past in EWB. There is so much talent around me, it’s overwhelming! I feel privileged to be in a position to harness all this potential and move us toward an impactful change in the agricultural extension sector. I may not be leading the way with my vision, but I have no doubt that we’ll get there. How could I, when I have an amazing team-ful of talents at my fingertips?

Challenging Perspectives – Extending a Hand Up

Challenging Perspectives is EWB Canada’s annual holiday campaign to combine fundraising and outreach. You can also read my Perspective below here and make a donation. Click here to browse some of the other perspectives.

When I first came to Ghana in March 2010, I lived with a host family in a village called Zuo. The head of the family is a farmer named Salifo. He is more educated than most of his neighbours. He can read and write in English and do simple math. He is a teacher at the local kindergarten, a community health volunteer, and helps run the local shea butter soap production group.

But when it comes to farming, Salifo doesn’t do well. One day last summer, I sat down with him to analyze his farm from the previous year. He’d grown 3 main crops: maize, rice and groundnuts. I asked him how much money he’d spent on growing these crops. From his memory, he listed out precise figures of his investments in seed, fertilizer, tractor services and labour. I wrote each number down under the corresponding crop. Next, I asked him how many bags he’d harvested from each crop, and the price he’d sold them for. Again, he listed the numbers from memory, and I wrote them all down. Finally, we arrived at the crucial step, the one he’d been avoiding: calculating his profit.

Maize: -293GhC

Rice: -204GhC

Groundnuts: -4GhC

In total, Salifo had lost 501GhC (about $375) on his farm that season. And that doesn’t include his own time and labour.

Why did Salifo lose so much money? There are three contributing problems:

- His farming skills and knowledge are poor. Salifo may be an educated man, but he doesn’t know how to get the most out of his farm. He needs to learn about the basic techniques that will improve his productivity: use improved seed, plant in rows, apply the right fertilizer at the right time, and respond quickly and appropriately to pests and disease.

- He doesn’t have a business mindset. Salifo is so many things, as I mentioned: a teacher, a community health worker, a volunteer, and a farmer. But he is not a business man, at least when it comes to his farm. He needs to learn some basic business skills: record-keeping, marketing, profit calculations and decision-making.

- He can’t control nature. Alright, this one isn’t his fault. He lives in an area with poor soil fertility and unreliable rains. But this means his risk management skills need to be even better – he cannot rely on his rain-fed farm to sustain his family.

This is a tragedy. Thousands, if not millions of farmers in Ghana are suffering from these same skill deficiencies. But there is a solution: effective agricultural extension services.

In order to profit from their farms, farmers need at least 2 things: 1) information on how to farm, and 2) business skills. Agricultural extension provides both of these things. (They also need input and output markets; see EWB’s Agricultural Markets team’s work for more!)

Traditionally, the government has hired Agricultural Extension Agents (AEAs) who go out to the villages to teach farmers about new technologies and practices. However, with new Information Communication Technologies (ICT) such as video and mobile phones, there is room for innovative new solutions to increase the reach and impact of extension services to farmers.

Ultimately, effective extension services come down to farmer behaviour change. This is an area where EWB has both experience and expertise. Drawing on our history of success with the Agriculture As a Business tool, we are developing new tools and approaches to improve technology adoption and behaviour change in farmers using innovative new technologies. Check out some examples here and here.

I know many of you have supported my work in the past. I sincerely thank you for that – your donation has made a difference! I have personally stepped up my commitment to the cause this year by becoming the Manager of EWB’s Public Sector Agriculture team in Ghana. I am asking you to also step up your commitment by contributing this year to my fundraising campaign!

Your donation to EWB will allow us to keep exploring and developing these tools to help farmers like Salifo to make a profitable living from their farms. I personally believe that we are making an impact through our work, from the farm right up to the policy-makers. But we need your donation to keep it up! Whether $5, $50 or $500, your donation will make a difference.

To make a donation, please visit my Perspectives page here.

Thank you all for your support – past, present and future!

A Tale of Two Projects

This is the story of two projects, one MoFA office and a case of bad coordination.

In early 2010, a prominent project came to my office, the Tamale Metropolitan office of the Ministry of Food and Agriculture. One of the project’s aims was to provide training and inputs to farmers in a bid to increase production (this is a VERY common project design in northern Ghana). They wanted to enlist the help of our Agricultural Extension Agents (AEAs) to carry out the implementation, in exchange for a small sum (also very common). The first step was to form groups of 50 farmers, each with one acre of land to contribute toward the project.

But it was not enough to just identify the farmers and their land. Like every project, this one was required to communicate their progress back to their funders in the West. As part of their monitoring, they had to send back a GPS map showing the location of every piece of land that was part of the project. That is 50 one-acre farms per farmer group, with anywhere from 1-3 groups per AEA, for 20 AEAs. That’s about 2000 individual one-acre farms, all shown on a GPS map.

And who do you think had to do that mapping, to go out into the field and walk around the perimeter of each farm with a GPS unit in hand? That’s right, the MoFA AEAs.

With only two GPS units in the office, this mapping procedure dragged on for months. Some AEAs only took half the data, while some managed to avoid doing it altogether. But eventually, the project kicked some butt and all the AEAs finished the mapping. Hours and hours of fieldwork, all to send a progress report to a donor in the West who probably won’t even look at the map.

Later in 2010, another project came to visit my MoFA office. This project was focused more on market linkages than training farmers. They were aiming to develop a database containing information for marketers – farmers’ names, contact info, location, main commodities, volumes, etc. They were looking for some sample data to populate their database and they had selected the 50-person farmer groups set up by the first project to use as the sample data.

One of the pieces of data required for the database was the GPS coordinates of the farms. The project brought one GPS unit and asked the AEAs to go around to each farm and mark it on the GPS. Of course they would provide a small sum for this work to be done.

No one protested. They took the money and did the EXACT SAME WORK ALL OVER AGAIN.

During the time taken to collect GPS data, whether for donors or marketers, the AEAs were not fulfilling their core role as extension agents. Their time was taken up by projects, away from solving farmers’ problems, away from responding to farmers’ needs and away from delivering agricultural information. The AEAs were used as information-gathering tools, rather than a means to actually reach out to farmers. And this was not just one day – this was weeks and weeks of work. You can imagine my frustration at finding out that this was done not once, but twice in the same year.

The development industry is a funny thing. Here in Tamale, several NGOs exist solely for the purpose of bidding on and implementing donor projects. They don’t have one specific mission, they don’t do their own project design, and they aren’t particularly discerning in the types of projects they bid on. They’re in it for the money.

So what’s the kicker in this story? These two projects were implemented by the EXACT SAME NGO. The project staff sat next to each other in the same office, but never talked enough to know that they were collecting the same GPS data.

Sustainable Food Security: Agricultural Models for the 21st Century

This is a post for Blog Action Day (#bad11), a movement that aims to start a global discussion through thousands of blogs posted in one day on the same topic. This year, the topic is one dear to my heart: Food. I have been thinking about food a lot for the past 1.5 years through my work in agriculture with EWB. We are working closely with the Ghanaian Ministry of Food and Agriculture to reach out to farmers, but what are we working toward? This question has nagged me more and more as time goes on, to the point that I ran a learning session at our last EWB retreat with the same name as the title of this post – Sustainable Food Security: Agricultural Models for the 21st Century.I’ve been reading a lot on this topic in the past 8 months. I’m not sure if there’s a trend toward addressing this issue lately, or if I’m just noticing the articles because I’m finally looking for them, but there is a LOT of writing out there! I’ve summarized a few of my favourite articles in the “Further Reading” section at the end of this post.

I have been thinking about food a lot for the past 1.5 years through my work in agriculture with EWB. We are working closely with the Ghanaian Ministry of Food and Agriculture to reach out to farmers, but what are we working toward? This question has nagged me more and more as time goes on, to the point that I ran a learning session at our last EWB retreat with the same name as the title of this post – Sustainable Food Security: Agricultural Models for the 21st Century.I’ve been reading a lot on this topic in the past 8 months. I’m not sure if there’s a trend toward addressing this issue lately, or if I’m just noticing the articles because I’m finally looking for them, but there is a LOT of writing out there! I’ve summarized a few of my favourite articles in the “Further Reading” section at the end of this post.

The Issues

The Issues

First, let’s get to the heart of the issue: it’s a matter of food production vs. environmental sustainability. Traditional industrial agriculture has achieved record production through intensive farming practices, mechanized farming and petro-chemical inputs applied with machine-like precision. This has come at the expense of the environment, with corporate farms using up precious fossil fuels and destroying ecosystems in the quest for more food. However, viewing these as two opposing goals is a false dichotomy; if we want to achieve food security far into the future, we must find a way to fulfill both of these goals AT THE SAME TIME! My research into this topic has tried to answer this question: what model of agriculture will allow us to achieve sustainable global food security?

Development workers have a unique perspective on the problem of global food security because we must take into account an additional question, “what is good for poor farmers?” In this case, it’s not just about achieving adequate food production, or nutrition levels, or even environmental sustainability. We must also take into account the lifestyle of the poor Ghanaian farmer, who is being asked to adopt this model to continue providing food for his fellow citizens. What model of agriculture will spur human development in Ghana while also fulfilling the above two goals?

Though I mentioned that there are a lot of people writing on this topic right now, there is a relatively low level of consensus as to what the future model of global agriculture should be. There is a never-ending number of models being promoted (organic, agroecology, industrial, urban, etc.), each with its own convincing arguments and promoters. This is quite startling, and makes it very difficult to choose one agricultural model to promote in our work. So how can we plan for the future?

Let’s be very clear here: the following are my personal opinions, not those of EWB, Ghanaian farmers, or anyone else you might confuse me with. There is no right answer, only a series of thoughts and questions that remain to be determined.

Traditional agriculture in Ghana is somewhat organic, in the sense that there are no chemicals applied to the crops. Most farmers practicing these traditional methods also don’t use improved seeds, proper land preparation techniques or any other Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs). As a result, they get low yields compared to their neighbours who use “modern” techniques – mechanized land preparation, chemical fertilizers/herbicides/pesticides, and better GAPs. This is leading Ghanaian farmers to see chemical agriculture as the way forward, when in fact many of these GAPs applied to their traditional organic fields would also increase yields significantly.

Right now, MoFA is steering Ghana toward a future of intensive industrial agriculture through credit-in-kind schemes and input subsidies. And why shouldn’t they? This is the path every other industrialized nation has taken to get out of poverty and push forward their economies. But I think it’s too late to take this path. The time has come when oil-based agriculture is getting too expensive (and oil prices are too volatile) to rely on. The price of oil will only increase in the next 20 years, so why are we promoting a model of dependence on these inputs in Ghana?

Right now, MoFA is steering Ghana toward a future of intensive industrial agriculture through credit-in-kind schemes and input subsidies. And why shouldn’t they? This is the path every other industrialized nation has taken to get out of poverty and push forward their economies. But I think it’s too late to take this path. The time has come when oil-based agriculture is getting too expensive (and oil prices are too volatile) to rely on. The price of oil will only increase in the next 20 years, so why are we promoting a model of dependence on these inputs in Ghana?

If things go ahead as MoFA wants them to, soon the majority of Ghanaian farmers will be using industrial agriculture methods. Food security in the country will be improved, but for how long? Soon fuel prices will be too high for Ghanaians to afford the food produced in this manner, and we will be thrown back into food insecurity. Ghana is at the brink of “maturity” in agriculture, about to choose a method to promote and follow for decades to come. Let’s help them make an appropriate and sustainable choice.

My colleague Mina works with an organic fertilizer company near Tamale and often cites a study that showed yields to be virtually the same when appropriate amounts of chemical and organic fertilizer were applied to test fields. In fact, the plot with the highest yields used a combination of both types of fertilizer. So why are these methods most often presented as mutually exclusive?

My colleague Mina works with an organic fertilizer company near Tamale and often cites a study that showed yields to be virtually the same when appropriate amounts of chemical and organic fertilizer were applied to test fields. In fact, the plot with the highest yields used a combination of both types of fertilizer. So why are these methods most often presented as mutually exclusive?

There are many sustainable practices being used in Ghana on a small scale – sustainable land management, soil fertility techniques, inter-cropping to naturally get rid of pests, organic fertilizers and weedicides and many other GAPs. What are the best ways for EWB to promote these techniques without being paternalistic and dictating the way forward for Ghana’s agricultural development? Tricky…

I think one of the key lessons here is that we need to be adaptive, changing our approach depending on the conditions (economic, social and environmental) in which we find ourselves. Of course, these conditions are changing all the time, so we need to be constantly testing our assumptions, checking if the information we gathered 1 year, 6 months or even 2 weeks ago is still relevant today. And we need to help the Government of Ghana to have the same resilient approach, adapting to new information and conditions as the world lumbers toward a new model for sustainable food security.

More Details

More Details

Different levels of thinking about this:

- Global food systems

- Consumers in Canada

- African agriculture

- Farmers

- EWB’s stance

- Our strategies

More questions to ponder…

- How do we bridge economic development & environmental sustainability in Africa?

- What are the pros and cons of each agricultural model?

- How do these changes in policy translate to realities on the ground?

- What stance should EWB and other NGOs take on these issues? How will this effect our work?

Other tricky issues (you can Google these for more info):

Other tricky issues (you can Google these for more info):

- African land grabs

- GM crops

- Foreign investment

- Subsidies

- Food price volatility

- Climate change

- Famine

- Biodiversity

- Farmers’ rights

- Biofuels

Special report on the future of food – population, development, environment, politics, nutrition, food waste:

- ‘A Prospect of Plenty’. The Economist, Feb. 24, 2011. http://www.economist.com/node/18200642

Politics, global markets, demand for food:

- ‘The new geopolitics of food’. Foreign Policy, May/June, 2011. http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/04/25/the_new_geopolitics_of_food?page=full

Olivier De Schutter, UN Special Rapporteur on the right to food, and the concept of agroecology:

- ‘Save climate and double food production with eco-farming’. IPS, Mar. 8, 2011. http://www.ips.org/africa/2011/03/save-climate-and-double-food-production-with-eco-farming/

- ‘Sustainable farming can feed the world?’. New York Times, Mar. 8, 2011. http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/03/08/sustainable-farming/

Agroecology and development:

- ‘Can the world feed 10 billion people?’. Foreign Policy, May 4, 2011. http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/05/04/can_the_world_feed_10_billion_people?page=full

Organic farming:

- ‘Study debunks myths on organic farms’. Star Phoenix, Sept. 27, 2011. http://www.thestarphoenix.com/business/story.html?id=5462520

- ‘Organic agriculture: deeply rooted in science and ecology’. Grist.org, Apr. 21, 2011. http://www.grist.org/sustainable-farming/2011-04-20-eliot-coleman-essay-organic

- ‘On agricultural productivity and food security’. Ed Carr, Open the Echo Chamber. Sept. 26, 2011. http://www.edwardrcarr.com/opentheechochamber/2011/09/26/on-agricultural-production-and-food-security/

Concentrated industrial vs. wide-spread “nature-friendly” agriculture, which is better for the environment:

- ‘Farming: Thoughts on an intense debate’. BBC, Sept. 2, 2011. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-14761015

Smallholder farmers and environmental sustainability:

- ‘Global food crisis: Smallholder agriculture can be good for the poor and the planet’. Guardian, June 1, 2011. http://www.guardian.co.uk/global-development/poverty-matters/2011/jun/01/smallholder-agriculture-farming-good-poor-planet

Findings of DuPont Advisory Committee on Agricultural Innovation and Productivity for the 21st Century:

- ‘Food security has global implications’. Politico.com, June 7, 2011. http://www.politico.com/news/stories/0611/56342.html

Moving from old to new models of agriculture:

- ‘A warming planet struggles to feed itself’. New York Times, June 4, 2011. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/05/science/earth/05harvest.html?_r=2&pagewanted=all

- ‘The farms are not all right’. Walrus, October, 2011. http://www.walrusmagazine.com/articles/2011.10-food-the-farms-are-not-all-right/

Update

Hi everyone,

Again, it’s been quite a while since I posted. Sorry about that! Life has been crazy busy lately, so I just wanted to post a short update about what life has been like lately.

August was an INSANELY busy month, with 6 summer students leaving (we miss you!), 5 new volunteers arriving, 2 weeks of meetings for EWB’s African Programs Leaders and… my 2-week Canadian vacation!

The 2 weeks of Team Leader meetings were held at the beautiful Lake Point Guesthouse on Lake Bosumtwe, near Kumasi, Ghana with ~10 super-inspiring leaders from EWB. The beautiful lakeside location provided an ideal place to step back from the day-to-day business of running an EWB team to think about our long-term strategy as an organization. Here are a few of the questions we discussed during the meetings:

- What are our theories of change within each team? How can we learn from each others’ experience?

- What are the investment criteria for EWB as an organization to invest in new or ongoing initiatives? What combination of results, potential and leadership needs to be in place?

- How can we invest more in EWB’s leadership pipeline, so great people continue to flow into our African Programs?

- How can we hire and use local staff effectively?

- What are various pathways to scale our change, either theoretical or from experience?

- What are the teams’ strategies for influencing the “big players” in their sectors?

- What is EWB’s overall vision? (We are currently undergoing a visioning process as an organization, pretty exciting to participate in!)

It was amazing to discuss these questions and to get/give feedback on our strategies. My brain was hurting! It was pretty intense – we even had a random woman buy us a round of drinks when she saw us working until 7pm on a Sunday, haha. Here are a few of my main take-aways from the meetings:

- Our team has come a long way! We were in a pretty rough spot last February, but we have really turned around and come back strong. I’m excited about the things we’re currently working on and can’t wait to see where another 6 months takes us!

- That said, I feel we have a long way to go in developing and articulating our strategy. These meetings were an AMAZING opportunity to push my strategic thinking and articulation further, so it’s something I’m passionate about pushing forward over the next 4 months. More to come on this blog!

- I think we need to invest a LOT more in understanding influence pathways for the agric sector (specifically public sector) in Accra. We’ve been trying to find out how to leverage our relationships, but there’s actually a lot of ground work that still needs to be done before we can do that.

- I’m also excited to build on more of the strong synergies between the 3 agric teams in Ghana – our public sector team, the Agric Value Chains team and Business Development Services. We’re all doing similar exciting things, and I hope we can find systematic ways of sharing and learning from each other.

- We really need to plan ahead, but it’s really HARD to plan ahead. Yeah, big learning, right? I’m being asked to project how many African Programs Staff we’re going to need in the next year, but it’s so hard to tell – will we still be searching? prototyping? scaling something up? doing a pilot in 2 districts, or 20 districts? At least I’m really happy to work for an organization that is so flexible and will allow us to adapt (to a certain degree) as things change. Pretty cool!

- EWB is exciting! We are developing a really inspiring model and I feel the African Programs vision is pretty inspiring as well. It makes me proud to work for such an organization and to be invested in the leadership of EWB 🙂

After the last day of meetings, I headed to Accra to fly to Canada. I arrived on a Saturday morning, was greeted by my lovely family, and whisked away to the cottage. It was spectacular!

After an exhausting month, 10 days at the cottage of eating, sleeping, drinking and dock-sitting was just what I needed. It was super-relaxing and we had beautiful weather (most of the time!).

After that, I returned home for a few days of errands, catching up with friends and visiting with my Gramma. It wasn’t long, and before I knew it (2 weeks to the day) I was back on a plane to Ghana! But I’ve arrived back feeling refreshed and rejuvenated, ready to dive into the “fall semester” – our busiest time of the year!

Of course this first week back in Ghana has been a bit nuts, trying to get caught up with everyone and everything. I’m working on the budget and “strategic plan” for our team for next year, which is difficult to say the least. But it’s been amazing to get home, unwind and unpack. Ben and I just moved to a new place right before I left for Kumasi. We’re still settling in, but so far it’s wonderful – both the house and the family we’re living beside. All in all, I’m getting ready for a great few months until Christmas!

It’s rainy season here in the north, and we were hit with a monster rainstorm yesterday afternoon. Don and I had a fun bike ride home from the office to discover that not only were all the dirt roads flooded, but the paved ones too! A few pics to tell the tale:

That’s all for now. Just a quick update! I hope I’ll be back to some more regular blogging soon – I’ve got a few in the pipeline that I’m looking forward to writing, so stick around!

Sacrifice

When I talk to people at home and tell them what I do these days, a lot of them comment on the sacrifice that I’m making. I often think to myself, am I really making a big sacrifice? Yes, I live far from my family and friends, but I live with the guy I love. Yes, I’m not making much money, but I’m not spending much either. Yes, I’m not building my career as an engineer, but was I ever goig to do that anyway? I’m 25 years old, managing a team of 9 people, determining the strategic direction of our work, building credible partnerships and interacting with major players in my industry. In what alternate world could I say all that 2 years after graduation from an undergraduate degree?

The truth is, I’m pretty lucky. This is a sweet job. I love my work, my colleagues, my hometown of Tamale. Of course I miss Canada sometimes, but for now I’m pretty happy where I am. And most importantly, I’m working at a job that is in line with my values, improving the lives of people living in poverty.

I have a lot of colleagues here in Ghana who are with me in the poverty-fighting business. In fact, NGOs are probably the largest industry in Tamale. I have more than a few friends with Bachelor’s degrees from the University of Development Studies in Ghana, and Master’s degrees in development-related studies from universities in Ghana and abroad. They are smart, well-educated and determined to help their fellow countrypeople. So are they making a sacrifice too?

The truth is, being a development worker in Ghana is also a pretty sweet job, in the more conventional sense. The pay is much better than any kind of government work, and tends to be more stable than business. It’s also a pretty safe career choice – in the job market, there are more positions for development workers than many other professions. I would compare the career path of a development worker in Ghana to that of an engineer in Canada in terms of prestige and compensation. In my opinion, these people are not making significant sacrifices in order to pursue their values. In fact, they’re pursuing a pretty stable and lucrative career path. But is this a bad thing?

On one hand, it makes me uncomfortable to see an industry that thrives solely on donated dollars. The basis of this business is people living in poverty; if this disappears, the entire industry disappears. But isn’t that what the industry is trying to do, eliminate poverty? This is a bit of a conflict of interest.

On the other hand, I think it’s wonderful that a career devoted to bettering the lives of others is so highly valued in this society. If I think about those careers back home – social work, non-profit sector, etc. – they aren’t valued nearly as much. Why is it that people who devote their lives to others are seen to be making a sacrifice? And why are they compensated accordingly? Shouldn’t we value more highly those who commit their lives to the service of others?

EWB is hiring!

Hello fine people!

Whether you’ve been a long-time loyal reader or you’re new to this here blog scene, I hope I’ve painted an exciting picture of this complex work we call international development. Now, here’s your chance to get involved: EWB is hiring!

—–

Positions Available now! To apply, go http://ewb.ca/volunteer

In Agriculture:

| Team | Position | Location |

| Agriculture Value Chains | Market Development Field Officer | Ghana, Zambia and potentially Tanzania |

| Market Development Project Manager | Ghana, Zambia and potentially Tanzania | |

| Business Development Services | Business Growth Specialist | Potentially Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania, and Zambia |

| Public Sector Agriculture Development | Seeker of New Models for Impact | Ghana |

| Public Sector Agriculture Development | Leadership Development | Ghana |

| Entrepreneuriat Rural Agricole (Français) | Agriculture Capacity Building Officer | Burkina Faso |

In Water and Sanitation:

| Team | Position | Location |

| Water and Sanitation | District Capacity Development and Decentralization Policy Analyst | Malawi (This position is only available in the winter, not the fall. The start date will be in February 2012.) |

In Governance and Rural Infrastructure:

| Team | Position | Location |

| Governance and Rural Infrastructure | District Capacity Development and Decentralization Policy Analyst | Ghana |

What does it mean to be an EWB African Programs Staff (APS)?

These volunteer positions provide APS with incredible opportunities for professional growth as a social change leader, all while creating lasting impact in rural Africa. Being an APS means working with purpose, collaborating with African partners, and having a life-changing experience. EWB’s African Programs Staff are humble entrepreneurs that become powerful change agents working as part of a larger movement for Africa.

What do APS do?

All of EWB’s work is designed to help our local partner organizations do what they do better. Our APS add value to partners in a variety of ways including executing on project specific work, building management capacity, improving learning and accountability systems, increasing skills of field staff and creating stronger connections between different stakeholders.

Where are APS working?

EWB is currently working in Ghana, Malawi, Burkina Faso, and Zambia, and with new projects in Tanzania and Kenya.

—–

Maybe you’re thinking, “but I don’t know anything about development” – no problem! EWB has one of the best pre-departure and in-country training programs around. You will be a junior development expert within months, armed with a continuous learning mindset to keep adding to your knowledge base.

Maybe you’re thinking, “but I’m a development professional, I’m not sure about volunteering” – no problem! Are you sick of working in a bureaucratic organization that stifles your creativity? Do you wish you had the freedom to go out and explore your own ideas? Are you fed up with the way the development industry works? So are we! EWB allows development professionals to gain hands-on field experience leading their own initiatives while working to change the way development happens. That’s an opportunity.

Maybe you’re thinking, “but I’m old, this seems like an opportunity for young people” – no problem! EWB hires staff from all walks of life, from new grads to professionals with 20 years of experience. If you have the right attitudes, you will fit right in to our energetic, hard-working and resourceful teams.

Maybe you’re thinking, “but I don’t know if I can handle living in Africa” – no problem! Trust me, you can do anything if you put your mind to it and you’re well-prepared. You will challenge yourself in ways you never have before and you’ll come out the other side with the experience of a lifetime.

Maybe you’re thinking, “but I don’t know whether I’d be good at it” – no problem! That’s for us to decide 🙂 Apply and find out if the fit is right!

—–

When do I need to apply? When do these positions begin and end?

Applications for all of the above positions are due on July 3rd, 2011. Within two to four weeks of this closing date, all applicants will be contacted and interviews with selected candidates will begin. Training and departure for these positions will begin in mid-October 2011. All positions require a minimum commitment of one year.

Not ready to make the commitment yet? Don’t worry. EWB opens new rounds of applications several times a year. Think about what this opportunity means for you, then check back for the next round of applications!

How do I get more information? How do I get involved?

- To apply, go http://ewb.ca/volunteer

- See http://my.ewb.ca/posts/86606/ for more detailed descriptions of the open roles.

Of course, if this sounds like an exciting opportunity but you have questions or concerns, please get in touch using either the comments section or the Contact form in the tab above. I’m happy to talk to anyone about my amazing job and your opportunities to work with EWB!

—–

Details on EWB’s work in Africa

Having Impact in Governance and Rural Services

EWB believes in the potential of public services such as water, education, and agriculture extension and ensuring that people who aren’t yet well connected to markets can still get the support needed to grow their business and raise a healthy family. EWB is working with governments who are far ahead in terms of decentralization and minimized corruption (currently this work is happening in Ghana and Malawi). We work with them to continue the process of decentralization. We work with them to develop state of the art monitoring tools that can guide resource investment at all levels. We work with them to invest in their management and field services to ensure that the services provided are backed by talented leaders.

Creating Change in Agricultural Businesses

In Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania and Zambia, EWB is investing in the agriculture sector – the main employer and export earner in most developing countries – as a way to unlock African prosperity. Historically, Western aid has focused on dispersing subsidized fertilizer, hybrid seeds, and machines, or purchasing products from farmers as a functioning private sector would. Regrettably, these efforts simply distort markets and prevent private sector growth. There is no reward for the innovation and risk required to work in the private sector, so the cycle continues. So EWB is addressing the underlying issues, working with existing organizations that have the ability to greatly impact the agricultural sector, fostering entrepreneurial, private sector growth and helping farmers develop new business skills. These organizations include – NGOs, private businesses, impact investors and major donors.

Driving Results in Water and Sanitation

EWB believes that the persistent water and sanitation challenges in Malawi, and in much of the rest of the developing world, are due to inefficient investment rather than lack of investment. EWB realizes that while drilling wells is an important part of the solution, it will never be long-term without a systemic approach. So EWB focuses on changing the system to support these outputs. One example is the creation of a simple water-point mapping and monitoring system that relies on coordination withexisting government programs to get the data. In short, it identifies broken outputs, the places where new outputs are needed most and the best location for them (strong water supply). The water mapping system is now functioning in 11 out of 28 districts in Malawi with plans to expand countrywide. EWB is also working with the government and communities to create functioning business models for water delivery, then sharing their findings within the sector and with the national government, influencing change.

Become a part of this important work by applying for one of the unique new African Programs Staff (APS) positions available in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania or Zambia.

Big John’s Self-Help Super Microfinance Scheme

Meet John Alhassan I. He is an Agricultural Extension Agent (AEA) at my office of the Ghanaian Ministry of Food and Agriculture. His job is to deliver agricultural information to farmers in his operational area and to help them improve their farms, whether that means reducing the level of poverty in a household by adopting better agricultural practices, or helping commercial farmers to get in touch with the market. John sees all types of strengths and needs in his daily work as an AEA.

One of the farmer groups that John works with is a women’s group of 24 members. He started building up this group using EWB’s Agriculture As a Business program last June. Through the program, group members were encouraged to contribute group savings to a bank account that John had helped the group to open a few years ago. Each member contributes 50Gp (about $0.35CAD) per week. After a few months, the group had built up their savings and they were ready to invest.

John was concerned that the group was too large to give a loan to each woman. If they divided the savings 24 ways, it wouldn’t really make a difference. Instead, he divided the group into four groups of six women each. He randomly selected one group to receive loans first by drawing the numbers 1-4 on pieces of paper and selecting one from a pile in front of the women. Each of the six women in the first group received a loan of 100GhC (about $65CAD) to invest however she wanted, but with the understanding that in two months time she would have to pay back the full 100GhC, plus 5GhC of interest. Most of the women are processors, so they elected to invest in bulk purchases of rice, groundnuts or shea nuts to process and sell at a profit. After two months, 100% of the money and interest were paid back to the group bank account, and the next round of loans were given out to six new women.

After each group had received the loan once, John upped the stakes – the next round of loans were for more money (120GhC), but the interest also increased (10GhC). Again, the repayment rates have been 100% so far. The group is currently on this second round of loans and their bank account balance is still increasing. The women are dedicated and determined and John is encouraging them every step of the way. The goal is to make enough money for the group to buy a grinding mill, a purchase which will give them an even higher return on investment.

Why do I think this is such a great story?

John is really passionate about helping people in his role as an AEA. Though many farmers have been trained over the years to sit around and wait for government money to come, John knows it isn’t coming any time soon. He also knows that the banks aren’t often willing to help; he already took this women’s group to the bank for a loan and they were rejected. Help isn’t coming from outside, so John is helping the group to help themselves. This group is serious, dreaming big and working hard to achieve their goals.

John has now taken this scheme to other farmer groups, where it is also working successfully. But why is he so successful in this approach? There are a few key elements of this grassroots project that have made it work so far:

- There is no time limit on this project. This is John’s own initiative, so he has taken the time to build up and groom his farmer groups until they are ready to handle serious money. He is not under pressure from donors or banks to report quarterly on his progress, and his funding isn’t going to dry up in 3 years. Instead, this home-grown approach gives the group and the AEA time to build up their skills and capacity to handle these loans.

- The group members have a personal relationship with John and a high degree of trust in him. He visits the group often to check in on their progress, encourages them when they need a kind word and keeps them accountable to each other. He hasn’t just come in to tell them what to do “for their own good”, but he has taken the time to build a trusting relationship with the group.

- The approach is tailored to the needs of the group. This isn’t some monolithic project coming in and prescribing a microfinance approach to fit all smallholders. Instead, it’s one AEA who knows the nuances of this group and has created a program that will work specifically for them. He has decided on the timing, the group sizes and amounts of the loans in collaboration with the group so that it best fits their needs. And this completely changes for each of the groups he works with.

This is an approach that is working for John’s farmers. Of course, it wouldn’t work if you tried to scale it up. It would be too complex, with too many variables and little things that would invariably go wrong – the farmers don’t trust the facilitator, the groups are thrown together to access loans, the money is too much or too little, the ToT didn’t teach trainers to visit the groups often enough. Farmers are smart – they’ve seen it all before, and they know how to manipulate the system. If you tried to scale this project, it just wouldn’t work.

The beauty of this approach is that it was developed out of a clear need: to find financing for the group to meet their goals. It’s a tailored approach that is based on a strong relationship between the AEA and the group members. The problem presented itself and the AEA was pushed to find a solution. In the development world, where we often find solutions in need of problems rather than the other way around, this is a refreshing turn of events.

I admire John for his dedication and creativity in meeting the needs of his groups. I wanted to highlight him as one of the many AEAs in the Ministry who are working tirelessly with inadequate pay and resources to do the best they can for farmers. These are the small beacons of hope that keep me motivated to keep working for change in the Ministry. John is truly an inspiration!

So I say, to all of you, keep doin’ it for Dorothy!

Strategy Development in small-meal-sized chunks: Part 2

Hey everyone,

Ben put up his second post in the Strategy Development series yesterday. It’s a long one, but very interesting if you like start-ups, frameworks, strategy, or just cool new ideas! I suggest you head over to The Borrowed Bicycle and take a gander. And once again, we’re looking for TONS of feedback on this stuff – does it jive? What do you like or dislike about it? What are we doing well, and what are we totally forgetting about? Please leave your comments over there, it will be an immense help to us!! Thanks!

Once again, the link is http://theborrowedbicycle.ca/2011/04/customer-development-and-our-strategy-process/. Enjoy!

Strategy Development in Small-meal-sized Chunks

Hello world,

I’m writing this post to introduce a new concept we want to try over here at EWB. I’ve been hanging out in the “international development/aid online community” for a while now and while it’s fun to chat, I’d actually like to put this community to work! (And yes, family, friends and colleagues, I want you to help me out too!) One of the favourite conversation topics is poorly designed development projects. While it’s fun to bash these projects, it’s harder to design good ones. I’d like to use this opportunity to seek out feedback on our team’s next move in public sector agricultural development.

This is an experiment! The plan is to outline our team’s strategy development process and the various investment opportunities we have, then seek external feedback on where we can invest and how we can play a bigger role in the agric sector. I have no idea if this experiment will work out, but I think it will be interesting to try! In order to work, it relies on a few success factors:

- lots of readers – so please share widely so we can ask for widespread feedback!

- feedback from within and outside the sector – if you know people in the agric development sector, send them this way. If you know smart people who would just be interested in providing feedback, please also send them this way!

- sustained readership – unfortunately there is a lot of info, so it’ll be going up in a series of posts – you gotta keep reading to get to the meat! We’ll see whether people can hang in this long.

- understandable posts – we’re looking for feedback on whether you have any idea what we’re talking about… so let us know!

As I wrote in a previous post, our team is currently undergoing a rigorous strategy development process. Thanks to Ben‘s personal interest in the tech start-up world, we’re trying something very new: applying start-up business principles to our strategy development. For a bit of background on why we’re applying these principles, see Ben’s earlier post, Tech start-ups and human development: different worlds?. Ben will introduce you to the tech-world language, but it basically advocates a Searcher rather than a Planner mentality – figuring out what people want before scaling it to a broad level.

Ben will be writing a series of blog posts in the next few weeks describing our process, model and some of the initiatives we’re looking to invest in. I’ll post links here on my blog, but please comment over on his blog – we’re hoping to get tons of feedback and discussions going!

So, without further ado, I will guide you to the first post over on Ben’s blog: Strategy Development in Small-meal-sized Chunks. Enjoy!

Evaluating Complexity

Warning for my non-development-worker readers: this post is a bit technical. But I hope I’ve explained everything clearly, and please ask questions if I haven’t! I would love to hear some new perspectives on this topic.

Also, I started writing this post a few months ago, when two big themes in the aid blogosphere were complexity and impact evaluation. People seem to be writing about this a bit less these days, but they’re still important topics (and we don’t have any clear answers) so it’s my turn to weigh in!

Where does all the money go?

So what is impact evaluation? This is the attempt to use rigorous methods to understand what actually works, or has impact, in aid and development. Of course there is no “silver bullet” solution to global poverty, but which interventions are more effective than others? Which things have no impact at all, or a negative impact? Ultimately, rigorous impact evaluation should lead funders and policy-makers to direct funds towards interventions which are most effective and reliable in improving people’s lives.

There is a huge push right now to “show what works” in foreign aid. Citizens are seeing that the Western world has spent trillions of dollars on foreign aid in the past 50 years, yet global inequality is worse than ever before. Of course progress has been made, but have the results justified the spending? Citizens want accountability from their governments, and proof that their hard-earned tax dollars are actually having a positive impact on the lives of those they are targeting in the developing world.

Many agree that the most rigorous form of impact evaluation today is the Randomized Control Trial (RCT). This technique takes a statistically significant sample size and randomizes selection into two groups: control and treatment. The treatment group receives a development intervention, such as crop insurance, or microcredit, or whatever you are trying to test, while the control group receives nothing. Both groups are evaluated over the course of the study (usually 1-5 years) and the results come out somewhere along the spectrum of “yes this works” (how?) to “this has no effect”. Sometimes it’s inconclusive, or the results are not easily generalizable, or there is further research to be done, but RCTs are generally considered the gold standard in evaluating development interventions.

There is a lot of controversy around RCTs because of the high cost and time involved. These studies are not appropriate in all cases. They shouldn’t be used by organizations looking to evaluate past programs, or smallscale projects looking for continued funding. Instead, RCTs should be used to inform development and foreign policy on a large scale. Citizens giving foreign aid want to know, for a fact, which development interventions are the best bang for their buck – and RCTs should, in theory, be able to tell them.

Inside the black box

The second trend these days in the blogosphere is complexity, or complex adaptive systems. Aid on the Edge of Chaos has a good round-up on complexity posts. The bottom line here is that in a complex system, results are unpredictable. The system is not static, or linear, or deterministic; it evolves over time, adapting and growing based on both internal and external influences. When dealing with a complex system, you need to take a “systems approach” by monitoring the whole rather than the individual pieces.

What does this mean for development? Well, people and communities and indeed the world are all complex systems. It is hard to predict when something will change, as we’ve seen with the recent wave of revolutions across the Middle East. From this perspective, it is hard to ever know which development interventions will achieve the results we want.

Most development interventions are designed around something like an impact chain – what will you do, and what results will it produce? However, complexity theory tells us that we should monitor a system generally for results, not just for our predicted or desired results. There are often unintended results of our actions, sometimes negative and sometimes positive. In addition, it can be hard to attribute positive changes to our particular intervention in a complex system – so much is happening at once and there are so many stimuli to the system, you never really know where something originated. This also poses problems when we’re discussing replicability of development interventions – just because something worked once in a particular set of circumstances, doesn’t mean it will work again in a different setting.

So what does it all add up to?

Impact evaluation and complexity. Now it’s time to bring these two concepts together. The big question here is this: Can we understand “what works” in enough detail to be able to predict future results of our interventions?

My answer is yes, but maybe not in the way you’re thinking. In the past, evaluation has usually focused on the question “what intervention worked?” where the answer is “fertilizer subsidies” or “school feeding programs”. I think we need to start looking more at HOW things work. Instead of looking for programs that we can replicate across entire regions, we should be asking, “what worked?”, “under what conditions?” and “with what approach?” which give answers more like “foster innovation”, “promote local ownership” and “give people a choice”. These conditions may be found across many different areas, but may have more of an effect on the success of an intiative than the WHAT of the initiative itself.

I generally support rigorous impact evaluation for 2 reasons:

- fostering a culture of accountability to donors and stakeholders (and taxpayers);

- foster learning so that we understand conditions for success and can set projects up for success in the future.

I think the aid industry has learned (and can learn even more) something about what works, or probably more about what doesn’t work. I also think aid can’t be prescriptive since human beings are complex and our behaviour is irrational and unpredictable. But we can set conditions for success when designing our interventions. And while the results may not be wholly predictable, at least the intervention will be more likely to succeed.

What does this look like in practice?

We are currently in the process of team transition and strategy re-development. Here are a few principles I’m looking to follow with our team strategy as we go forward:

- always have a portfolio of initiatives on the go (don’t put all your eggs in one basket)

- make sure these initiatives all contribute toward the bigger change we’re trying to make in the agric sector

- range of timescales: short-, medium- and long-term changes, informing and building on each other

- constant learning and iteration: testing, getting feedback, adapting, and testing again

- focus on articulation of our observations and learning to external audiences

- high awareness of the system as a whole: what does it look like? where are the strongest influences? the most volatile players? who exerts the most force on the system?

What principles would you add to my list?

The Donor Effect

Yesterday I had the chance to meet up with Mustapha, my colleague at MoFA and one of our star field extension agents. He has just returned from a trip to Canada, where EWB (with CIDA’s support) brought 18 of our African partners to participate in our annual National Conference in Toronto. In addition to attending the conference, the African delegates were set up with placements related to their field of work. Mustapha had the chance to visit the University of Guelph’s agricultural college, OMAFRA and Agricorp, as well as an organic dairy farm and a commercial pig farm. These were all really valuable opportunities for him to expand his knowledge of farming and learn about new perspectives and practices. He was like a sponge, soaking it all up. And he had a great time!

But one story he told me has me a bit troubled. On one of his placements, he had the chance to meet with a group of local religious leaders (or “elders”, as he described them). This group wanted Mustapha to tell them what he thought was needed to improve the livelihoods of Ghanaian farmers. Mustapha mentioned inputs like seed and fertilizer, and also shared the fact that many of his colleagues are trying to do their jobs without adequate transportation (motorbikes). He talked about the need for credit in order to grow an agribusiness, even at a small scale.

I guess they were impressed because upon leaving the community, Mustapha was presented with an envelope containing $500. He was told that this money was to “help his farmers” in whatever way he saw fit. “If you do well, there will be more where that came from.”

When he reached my office yesterday, Mustapha was obsessed with finding the right use for this money. Should he use it to buy fertilizer and give it out on credit to his farmers? Should he use it to promote vegetable production? What about giving it as a loan to a women’s group he works with? He was throwing out ideas and asking for my opinion, stating, “I need to report back to the people in Canada this week on how I’m going to use the money!”

And there it was. Mustapha was under pressure to report back to his donor. It was taking him away from his real job, which at this time should be reconnecting with the farmers in his operational area, whom he hasn’t seen in over a month, and preparing a presentation to share what he learned in Canada with his colleagues in Ghana. He wasn’t taking the time to investigate the opportunities, to find the best use for this money – instead, he had to find a quick way to spend it so he could report back. He wanted the funding to continue, so he needed to find a good use right away to reassure the donor he knew what he was doing. Even though using this funding represented only a fraction of the work Mustapha has on his plate, it was taking up all his time.

On top of that, Mustapha was at a loss as to how to actually give out the money – after all, an extension agent doesn’t usually have a lot of extra cash, so people would ask questions. He asked me whether EWB would be able to disburse it to farmers. I gently reminded him that we never give funding to our partners or the farmers we work with, as it erodes our trust relationships and changes the nature of our interactions. This is one of the core principles of the Agriculture As a Business program: farmers must choose to undergo the training knowing that there is no funding coming at the end.

Now, I know these people mean well. They want to do something, anything, to help the poor farmers of Ghana. They want to make sure their money is going to good use, not being eaten up by administrative costs or corruption. And they want to have a direct connection to the impact of their donation (a common sentiment and the reason sponsor-a-child campaigns are so effective). I’m sure they don’t realize the constraints they’ve now placed on Mustapha and his work.

But Mustapha is now a one-man aid organization. He is in the position of accepting a donation, figuring out how to use it for good, organizing all the logistics to make sure the recipients of the aid benefit from it, and reporting back to the donor. All while keeping up his real job as an employee of the Ministry of Agriculture (though the donor doesn’t care so much about that part, they’re not funding it).

This is a microcosm of the donor-recipient relationship. Rather than simply getting funds to go ahead and do their jobs, local NGO and government workers are under severe pressure to report back to donors for any funding received. This takes up an inordinate amount of their time and attention and can result in a decline in the quality of their real work in the field. I have now seen firsthand, from a friend and colleague, how donor funding can distort priorities and reduce the effectiveness of an otherwise excellent civil servant.

A Bitter Pill

As I near the 1-year mark of my work in Ghana with EWB, I’d like to reflect back on what has happened over the last year. We embark on these jobs and journeys with the hope of making the world a better place, of somehow contributing to “international development”. However, I’m forced to acknowledge that it’s unlikely that anything I’ve done in the past year has directly improved the lives of poor Ghanaians, and that is a bitter pill to swallow.

I know, that sounds really negative. But believe me, it’s not all bad! There are different types of impact we can have – from short-term, direct and focused to long-term, indirect and widespread. My direct impact this year was limited, but I’ve had impact in other ways. So please bear with me as I get to the end of this post – there is a happy ending!

2010 was a rough year for our team, alternately known as Team MoFA, Rural Agriculture Ghana or Agribusiness Ghana (we still don’t seem to have settled on a universal name). When I arrived last March, the team was undergoing a rocky Team Leader transition, which inevitably led to a short dip in team productivity. Unfortunately, we weren’t able to fully recover from the dip, and the new Team Leader stepped down in January, leaving a vacant place at the head of our team. We also went from being a 9-person team, when I arrived in March, to the current 4-person team – a huge loss of resources. Most of this was just due to people’s contracts being up and not enough new volunteers to fill their places, but it will still take some time to rebuild our numbers.

In terms of strategy, we haven’t seen as much success as we hoped with the Agriculture As a Business program (for more details on the challenges, please see my previous post). The political and systemic barriers in the Ministry of Agriculture are too imposing to lead a significant change in extension from the ground up, and we’ve been unable to influence the right people at the top. Volunteers in districts were getting demotivated by barriers that were out of their control, and all the high-level talk about mobilizing farmer groups didn’t materialize into any concrete changes in the sector (policies, funding, etc.)

We had an amazing group of Junior Fellows (students) from EWB join us in the summer, but they experienced many of the same challenges. They achieved a few fabulous short-term successes, yet on the whole were unable to institutionalize the Agriculture As a Business program in any of their Ministry of Agriculture district offices. We concluded that our current pathway for scaling the Agriculture As a Business program was ineffective and decided to reallocate resources to address district management challenges. A few Professional Fellows experimented in this domain, with varying degrees of success in individual initiatives, such as improving staff meetings, management styles, collecting feedback and time management strategies. But none of these initiatives promised the transformational change that we want to see in the way the Ministry of Agriculture is run from the top.

The one successful initiative I participated in this year was the DDA (District Director of Agriculture) Fellowship, a management and leadership program. It was a success in the sense that all the DDAs loved it, and tried to apply what they learned in the management of their districts. However, it’s really tricky to know whether this has trickled down to the extension staff and actually improved the work they’re doing in the field, with farmers. This is definitely more of a long-term change, a culture shift that will gradually result in improved staff performance. But evaluating these types of programs is really tricky, and attribution is very difficult, so… who knows??

The only direct impact I’ve probably had on poor Ghanaian farmers is through my personal interactions with my host family and friends in the village. I’ve treasured these interactions and really tried to be a good role model and influence. However, I’ve been hesitant to provide any form of material aid, beyond a few Christmas presents that I brought back from Canada, for fear that it will change the nature of our relationship. I did support the local women’s shea butter production group by buying 200 bars of soap to take back to Canada (it’s great stuff!), so I guess that cash injection probably made a small difference. But is that really the type of work I came here to do? No…

A few things I’ve learned in the past year:

- As much as we talk about effective program design, its often the operational capacity of an organization that is the bottleneck to achieving success: it’s amazing how much time and energy can be spent on just making a team function. I have great admiration for excellent managers, admin and support staff who, if they’re doing their job well, you don’t even really notice in your day-to-day work.

- It is unrealistic to achieve widespread impact in 1 year: we need to break 1-year placements down into specific “learning” or “doing” chunks so volunteers realize they’ve contributed something meaningful. For example, if we’re trying to make a big change in technology adoption through agricultural extension, a 1-year volunteer should have a mandate such as “learn about tech adoption techniques outside of the public sector in Ghana” or “pilot one new tech adoption approach with extension agents in your district and prepare a report with your recommendations for the team strategy going forward”. If they hit on a genius idea, great – we’ll scale it! (if there’s a scaling mechanism). If it doesn’t work, also great! share your learning and how we should change our approach in the next iteration of the strategy.

- Effective interventions (or inventions) only matter if there is a way to scale them (or sell them): you might have the greatest idea in the world, but it doesn’t matter if no one sees it. Transformative change needs to reach scale, one way or another!

- Perspective matters: even if you DO know what needs to be done, on the ground, to make a significant improvement to the lives of those living in poverty, you need to find a way of framing it so that it matters to those making the change, from the bottom (field staff) to the top (policy-makers). Just providing evidence to support your case is not enough; you must account for political, historical and social implications as well.

- Field realities are valued: EWB gets a lot of street cred for being “in the field” or “on the ground”, working in districts (not the most glamourous of job locations). We need to find better channels for sharing these field realities with those higher up the chain of command. (Suggestions?)

- Opportunity cost: there will always be more opportunities than you can take advantage of, the hard part is gambling on which opportunities will be most worth your time in the end.

- BONUS EWB lesson: it’s ok to fail, as long as you LEARN and CHANGE as a result! (check out http://admittingfailure.com for EWB’s recent initiative on encouraging learning from failure in the NGO world)

Now, as we peer out at 2011 with a couple months already in our pocket, our team is forced to admit that we’re not achieving as much as we’d like. While we can’t categorize the Agriculture As a Business program as a failure, since it IS an effective tool for building farmer groups and developing business skills, it’s not quite a success either, since we can’t get the Ministry of Agriculture to adopt it at the scale needed to achieve widespread change.

There has been a lot of talk about failure recently, and encouragement for NGOs to admit failure when it happens. But this is a clear example where the situation is not black or white, failure or success – but rather grey. In our team’s collective experience in Ghana, a lot of other NGOs/projects at this point would keep lauding their programs as successes and putting more and more resources into them. Instead, we want to acknowledge our lukewarm progress and shift to where we can have white hot results instead. It’s frustrating for our staff to keep banging our heads against the wall in a program that’s going against the flow of the current agricultural sector trends. We’re not giving up on this program; but until the stars align to facilitate the widespread changes that are needed (district autonomy, decentralization, performance incentives, etc.) it is more effective for us to invest our energy in other places.

We’ve now been working with districts in the Ministry of Agriculture in Ghana for 6 years. We’ve met a lot of key players, we understand the system, we’ve seen lots of challenges and we’ve built strong relationships. We’ve tried a few things, with varying degrees of success, but nowhere near the scale of change we want to create. Now we have a bunch of cool ideas, but we have no idea which one is going to work. In the spirit of complexity, we’re not going to throw all our eggs in one basket; instead, we’re going to explore the change potential of a number of different initiatives and gauge the reaction of those in the Ministry of Agriculture and in the wider agricultural development sector. I’ll be blogging more about this strategy development process as it unfolds, so you can all follow along with me!

Back to that bitter pill: my underwhelming personal success. Is this the kind of year I wanted? Of course not. Has it been a waste of time? Heeeellllll NO! I have learned SO much valuable information over the past year that will allow me to position myself to create the change I want in the coming 2 years.

You might think I’m demotivated. That I’m frustrated by the pace of change and our inability to see any real impact. That I’m ready to throw in the towel and truck back home to an easier job in Canada. But you’d be wrong! Strangely enough, I’m more motivated than ever! Something about being faced with so many challenges at once has really sparked a fire in me. I’m excited to drive the team in new directions, to get us excited about what’s next and to build ourselves up into an impactful, influential team of agric superstars! Seeing the passion and dedication of my fellow teammates has forced me to find renewed resources of energy in myself. I can’t wait to see where we go next.

Why I’m Here

A friend recently wrote me an email in response to my appeal for funds with EWB’s Challenging Perspectives campaign. He identified an inner conflict: he felt he should donate out of obligation to our friendship and feared that he would be ostracized if he didn’t, but was having trouble personally connecting with my work in Ghana. To donate, he felt that he should really believe in the work that EWB is doing (and I’m doing, through EWB) and be able to get behind it 100%. I most definitely agree!

This is exactly the kind of conversation I want to start with my Challenging Perspectives campaign. Why do we feel obligated to donate to charities when we really know little about what they do? How can charities make people FEEL something and personally connect people to their work? It’s a struggle on both sides.

In response to this email, I wrote back answering 3 questions:

- Why am I here?

- How am I feeling about it?

- What am I working towards?

Below is the email I sent back to my friend. I hope it answered these questions for him, and I hope it will for you too. Either way, leave a comment and let me know what you think!

—

1. I’m here because:

- I feel fortunate to have been born to an affluent family in a developed country and hate that it means I have so many more opportunities for happiness and success than so many other people in the world – I want to work to decrease global economic and “opportunity” disparity

- I feel guilty about being born in Canada and feel I have a responsibility to help others

- I believe we live in a globalized world where we’re all connected and will have deep impacts on how others live, whether through our consumer habits, environmental practices or political policies

- I think change IS possible in developing countries, specifically in Ghana from having spent time here, and I want to help create that change

- This is a pretty cool job that gives me good professional experience and is developing a lot of skills that I value (management, leadership, critical thinking, communication, etc.)

2. How I feel:

- Frustrated that change happens so slowly

- Unmotivated by some circumstances in Ghana (sexism, racism, kids not going to school, etc.) and some of the people I work with

- Incredibly motivated by some of the other people I work with (one of whom is an AEA who is hopefully coming to the EWB conference in January!)